I had climbed the hill just for the view. I bicycled past the low income

housing in this hard-luck neighborhood. I walked across the tall grass to the

summit.

I had climbed the hill just for the view. I bicycled past the low income

housing in this hard-luck neighborhood. I walked across the tall grass to the

summit.An American's thoughts on the American bombing of Saint-Etienne, France, May 26, 1944

Note: I wrote this in early 2004, before the publishing of "Le Bombardement de Saint-Etienne : Pourquoi?" by Marc Swanson. I now know that some information here is wrong, but I'm keeping it as it was. It shows how confusing it can be to find out what happened in WW II. In particular, I now know that the bombing was part of the much-opposed "Transportation Plan" lead-up to Overlord. Also, by November 1943, all of the "Hexagon" of France was occupied, not just the part known as Occupied France.

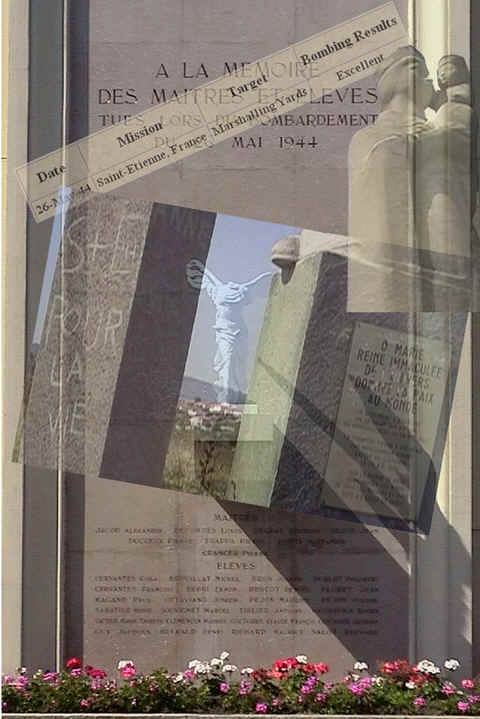

I was probably the first American to see the hilltop memorial on La Cotonne in Saint-Etienne, France. I had no idea. Maybe no American knew. I had no idea that schoolchildren were killed by their American allies here.

I had climbed the hill just for the view. I bicycled past the low income

housing in this hard-luck neighborhood. I walked across the tall grass to the

summit.

I had climbed the hill just for the view. I bicycled past the low income

housing in this hard-luck neighborhood. I walked across the tall grass to the

summit.

I had read of the "bombardment that killed 984 and destroyed 1100 buildings." The French are so subtle on this matter that only later I learned that it was an American bombardment.

I knew that Saint-Etienne was a strategic location even though there was no actual fighting anywhere near the city. It's the second best route from Paris to Marseilles on the Mediterranean Sea. The coal mines were still active during the war and there was a world-class arms factory. Saint-Etienne was in unoccupied France, the "French State" (État français) far from the front under the supposedly French-controlled Vichy government, but this region was too beneficial to the Nazis, selling supplies to Germany and providing relatively safe passage to the Mediterranean (although the Resistance was active in the area).

I gave little thought about the 984 victims. I had lived in France five months by then and had adopted some of the French thinking. C'est prévu. ("It's foreseeable" or "It's to be expected" or "You can bet on it" or "Whadja expect?".) If you're a country at war, then people die. And they were all military personnel for all I knew. And it seemed minor compared to the 6000 Stephanois soldiers who died in Word War I (there was no action near the city at all in that war). The monument to those dead is an imposing sculpture near the city center in Place Fourneyron. Six thousand young men! Devastating. We Americans think little of President Woodrow Wilson, who lead the U.S. into WW I. The Stephanois named the main street (Grand'Rue) by the City Hall after him. But I digress.

Now I was facing a memorial to schoolchildren. Did I misread the French? It makes no sense. That wasn't prévu. The view from the hilltop is beautiful; the memorial is haunting.

Since returning home, I have tried to make sense of the deaths. The official U.S. Air Force history website says that the target was the marshalling yards (railroad freight yards). Saint-Etienne was an industrial city then and had three rail yards, all near residential areas and all apparently targeted. The errant bombs in Tardy must have been intended for the rail yards by the coal mines, about a kilometer away. Blowing up an elementary school seems to be a mixture of bad luck and a mistake. It also seems that neither the American military nor any other Americans understands what happened in Saint-Etienne. One American account simply says that the marshalling yards were targeted with "excellent" results.

The shortest answer is that it was a high altitude bombing. Precision was not as important as avoiding antiaircraft fire. The 463rd and 464th Bomb Groups of the 5th Wing of the 15th Air Force of the U.S. Army lost no planes or crew that day. That was good because they had many more missions to fly to win the war.

"C'est la guerre." We Americans have no translation for that. There's an English expression, "All's fair in love and war," but it's used to justify foolishness in romance, not as an observation of war. "C'est la guerre" means that war defies logic so you shouldn't try to make sense of the suffering. In America, there's still a sense that war is logical.

Even at high altitude, the crews were hardly safe. Just the day before, the Lucky Lady was shot down returning from a mission over nearby Givors. All ten of the crew of the B-24 Liberator died, some slowly. A thoughtful French memorial to the crew is at Memoire-Net.org.

I read "Not the Germans Alone" (1999 Northwestern University Press) by Isaac Levendel (or Lewendel). His mother was betrayed by French collaborators and executed at Auschwitz, so he has good cause to be angry. He grew up near Avignon in southeastern France. When a boy shows him a downed British plane, he writes (page 110), "This was a British plane because, contrary to the Americans, the British were "not afraid to take more risks and fly low so they could hit the target precisely."

Levendel notes that the British pilot had died. He mentions no other crew. Maybe it was a Spitfire dive bomber. Those planes were not designed to fly at high altitude and were much more maneuverable than the U.S. heavy bombers. The B-17 Flying Fortresses had a crew of ten and a cruising speed of only 170 m.p.h. Today, French trains go faster than that (and are only slightly less maneuverable!). I don't think the heavy bombers had any choice but to fly high.

Levendel also gives an account of an allied bombardment on Avignon from his

perspective as an 8-year-old (page 95):

The bombardment did not feel or sound like it does in the

movies. The heavy smoke smelled like dust and fire. The explosions were much

more violent than I had expected. The earth trembled under my body, and I could

feel the shock wave of the explosions on my neck and chest, as if the bombing

were happening inside my shirt. Burying my head in the grass had no effect.

There was nowhere to hide. My mother had reached the limits of her power and

could do nothing more to help me.

Levendel's book is well worth reading, His research is excellent, but he did not research the military history. His perspective is not French, because his problems begin when his family is determined to be "foreign" Jews even though he was born in France. This was the only book I could find in local libraries that described Allied bombings on Free France.

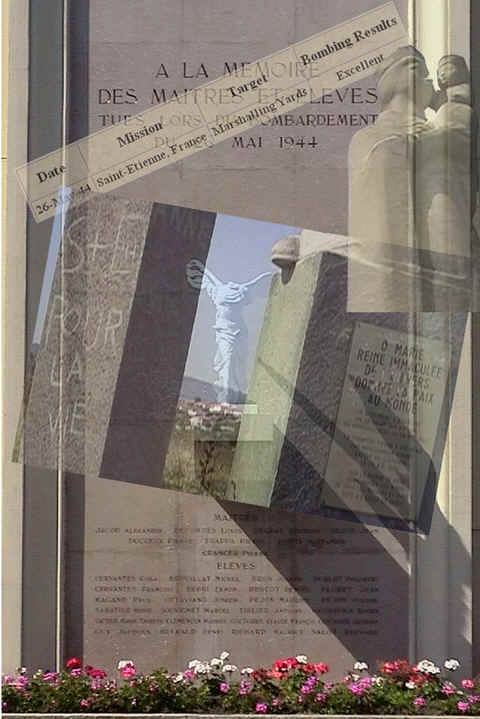

The Memorials

The hilltop Madonna-and-Child is clearly not intended to be visited. It's not landscaped and there are no benches or picnic tables. It's next to a low-income neighborhood. It's intended to be seen lighted at night from afar. I never saw it at night because you can't see if from la Place du Peuple, where we lived. Even when we went to la Place Jean Jaurès for a treat at the Oasis crêpe stand at night, the four-story buildings blocked the view.

The graffiti, "St E Pour La Vie," translates roughly as "Saint-Etienne Forever." The city is commonly called "St-E" (pronounced San[g]-TAY. That's "sang" without the "g"). Literally, it's "Saint-Etienne for Life" and I wonder if it's a bit of a play on words. Another possibility: This may be "S + E Pour La Vie", which may just be a declaration of romance of two people with the initials S and E. In any case, it's a friendly graffito.

At the school at the base of the hill, the centerpiece of the memorial is a miniature of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It's probably the third most popular exhibit at the Louvre in Paris, after the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo. I don't know what it signifies in this context. That day, wings brought suffering; the victory had a year to wait.

Another part of town that suffered greatly that day was Le Soleil (meaning "sun" but also a play on the family name "Soliez"). I once bicycled through Le Soleil, but saw no memorials as I passed through. I learned later that this neighborhood was also hard-hit. My source was the tourist-oriented book, "Saint-Etienne, la ville de toutes les villes," (see sources below). The entry for Le Soleil says "il connut le matyr lors d'un bombardement qui posa le feu et le deuil sur la ville." The book's translation: "it ... underwent martyrdom during an air raid in May 1944, when fire and death rained on the town." From that circumspect description, any American would assume that the source of fire and death was the Nazis.

Some reasonable conclusions

Americans should be proud of our role in the war. I certainly am.

America could do a better job at documenting World War II. Remembering the unhappy details doesn't reduce the honor of those who served. After all, c'est la guerre.

Americans should be more sympathetic to the French perspective. The French are extraordinarily grateful for the help we gave, but being liberated is no fun. C'est la guerre.

America needs to remember that the decision to go to war is a decision to kill innocent children. The unthinkable is unavoidable. C'est la guerre.

America should remember the innocents killed in World War II, perhaps as part of the new (May 2004) World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. I assure you, if one of our bombers had been shot down over Saint-Etienne, the local people would have erected a memorial to that lost crew. We Americans have to memorialize this sad part of the war because the French are too grateful and too polite to do it.

Some unorganized gleanings

Saint-Etienne was not alone. 70,000 French were killed by allied bombs.

Unfortunately, in English, "Tardy School" sounds like a joke. Tardy means "late," but its only common use is "late for school." So it sounds as if it's the "Late for School" School. An American might think that it's a special school for children who are always late for school. You can't simply say "the Tardy School" without risking a giggle. You've got to say that there is a neighborhood known as Tardy, which is a common surname and has nothing to do with the English word "tardy."

The bombardment here was just 11 days before D-Day (what the French call Jour J), but the bombardments in southeastern France had nothing to do with Operation Overlord. [see correction at top] It was apparently just part of a continuing effort to slow the Nazis. The bombings didn't even get a code name like "Overlord" or "Dragoon." It seems that the Allies bombed southern France as soon as air bases in Italy (around Foggia) fell into Allied control.

It was a noisy solemn view on July 1, 2002. The Tour Bleu (Blue Tower) was being demolished from the top down. This building was an old low-income housing project. I suspect that this area became a site of low income housing in the 1960's because it had been bombed out. This is still a low-income housing neighborhood. How many World War II memorials in France are in neighborhoods that were obliterated and are no longer historic and are therefore unattractive to us Americans? The grateful French will never tell us.

Click on the picture for a larger version. This panorama is stitched from

handheld video stills. I turned 360 degrees while filming and paused briefly for

each overlapping still photo (to avoid the blur from a steady movement).

Technically, this picture is not very good, but I am fond of it.

View of Saint-Etienne from the Cotonne memorial. The Saint Charles Cathedral

on Place Jean Jaurès (formerly Place Marengo) is at upper center. Click on the picture for a

larger version.

Sources-

http://www.463rd.com/data/463rdmissions.htm has a lot of detail about the 463rd heavy bombardment group and is my source for the report that the results in Saint-Etienne were "excellent." These are the men that flew around in those big, slow easy targets.

http://www.airforcehistory.hq.af.mil/PopTopics/chron/44may.htm is the May 1944 chronology on the official Air Force History website. You get a good impression of the magnitude of the war effort. Here is the entry for the Army's 15th Air Force based in Italy. (The USAF was not a separate division of the military until 1947.

05/26/44

Fifteenth AF

Almost 700 B-17's and B-24's attack M/Ys at SaintEtienne, Lyon, Nice, Chambery, and Grenoble.

Memoire-Net.org. A website on WW II in the Rhone-Alpes area (Lyon and Saint-Etienne) with a section on the bombardments there.

Not the Germans Alone, (1999 Northwestern University Press) by Isaac Levendel (Lewendel)

Saint-Etienne: La Ville de toutes les villes, (1988 Editions De Borée) by François Bouchut and Gil Lebois. A promotional book in French, German, and English. The English is comical, as if the translator used a French-English dictionary that might have belonged to Shakespeare. For instance, a forgotten author is called an "obliterated author" and s'attarder becomes "to tarry" (at L'Espace Giron) instead of "to linger." Nonetheless, the parallel English is helpful.

Discover Saint Etienne, (1996 Editions de la Taillanderie) by Philippe Chapelin. In English.

Photography and web page by Dan Axtell

Photos taken July 1, 2002

www.danaxtell.com/france

Please email me (in English or French) with corrections to my facts or my

French. I need all the help I can get.

danaxtell@

danaxtell.com

See also:

A memorial for the French

schoolchildren killed by American bombers.

Back to: Notes from Saint-Etienne 2002